Contents

So, you have some poems, or short stories or maybe even a novel. You all know about the Writers and Artists Yearbook, you've all seen stories and

articles that you could have written yourselves, so why don't you send things

off? Today we'll try to identify what's holding you back.

I'll talk first about general issues, then deal with the details about sending off, then what

to do after. I'm not going to deal with blockbusters - I'm going to assume you're

happy to start at the shallow end. If it all sounds like too much work, don't worry - I'll offer some shortcuts

at the end.

I suppose firstly we should look at the incentives to sending things

away.

- Money - Unless you regularly write articles, you won't get much,

but it's nice to get paid for something you enjoy doing (especially if you get paid £20 for a haiku). I still treasure

the £1 cheque I once got from the BBC.

- Fame - It's easy to be a big fish in the little

pool of poetry or short stories

- Participation - Ever read something and thought "I could have done that"? Going from being a reader to a writer is a big leap,

one you've already made. The next step is to become part of the writing community. It's a big step, like progressing from taking music lessons to becoming

a public "performer". By going to workshops and sharing your work you're

already well on the way to being a public performer. Now it's time to take the

next step and get published.

- Improving your writing - Even if you're just writing for your own

enjoyment, getting published can help. Writing without publishing is a bit

like talking to yourself.

- Angela Carter thought the writing process

incomplete until the piece was published.

- Poet Don Paterson wrote that "the poem begins with inspiration and ends in publication, not just completion"

- Jane Holland (poet and editor) wrote in April 2008 that "people learn

most about writing poetry from actually seeing their work in print. ...

Contrary to popular belief, new writers don't learn as much from sitting in

workshops ... To see a new poem in print is the best way

to learn, because you are far more likely to spot your mistakes once a poem is

set against others in a public context, and suddenly realise how to fix them"

- Because if you don't, others worse than you will!

To me nowadays publication is an integral part of the writing process.

The only

unpublishable pieces are those that aren't good enough - though some are

harder to publish than others

- Fear of boasting - I've published

137 poems,

16 stories,

14 articles,

2 reviews,

1 academic paper,

and 1 computer game, as well as various WWW stuff. How do you react to

me

saying that?

- Am I showing off? -

Modesty (false modesty especially) is something you'll need to

overcome. It helps neither you or your audience

- Is it all true? Even if it is, what

hasn't been said? How important are the magazines?

Why haven't I published a book? -

You don't need to make your CV into a confession! If you've won 3rd prize in a local

writers' group competition that makes you a "prizewinning author"!

- Fear of failure - Don't worry: only you will know. All the same, it

can be a "character-building" experience. Writing is used in therapy and self-esteem

courses, and the success of the writing can be confused with the success of the person. If you have low self-esteem you might have some dark periods on

your way to success. One way round this might be to have systems, mechanisms and

schedules in place so that you don't have to repeatedly motivate yourself to send things off - it becomes an automatic reflex.

Try to remember that successful people fail more often

than other people - the difference is that they keep trying!

- Dislike of marketing - In a "Paris Review" interview Kurt Vonnegut said that "In a creative writing class of twenty people ... six students will be startlingly talented. Two of those might actually publish something by and by". When asked what distinguishes those two he said "They will probably be hustlers".

Marketing doesn't come naturally to all of us. To be your own agent you may

have to take a drink or two. But you'll get used to it. Or you go into "P.A." mode

or Civil-Servant-mode, depending on your experience. Don't let it drain your

creative juices. You could keep your submissions folder separate from your

writing folder.

The excuse of wishing to keep your art pure, untainted by commercialism, is no

excuse at all.

- Fear of embarrassment once published - Use a pen name if you're worried that workmates or family might find out

- Fear of the expense - Well, mountaineering, horse riding or supporting

Chelsea isn't cheap either. Publication shouldn't be costly but you may need to

invest initially. It's recommended that you study a magazine before sending to it. Buying the magazines becomes expensive, but you can browse at Borders, Heffers, the University Library, or the Poetry Library at London. You may also be able to browse online. Postal costs shouldn't be an issue unless you're sending to the States. And there's

always e-mail

- Fear that your work/ideas will be stolen - It happens, though

rarely. It's one way to become famous.

- Fear that when your work's published it will be adversely reviewed -

if your work's ever reviewed, just be grateful!

- Fear that you're too old - you don't need to be young and beautiful to embark upon a writing

career. You can be 35 and still win "Young Novelist" competitions. You can be

over 40 and make a splash. Venessa Gebbie (from zero to story-collection in 4 years) and Helena Nelson (poetry)

burst onto the scene later in life and rapidly had many successes. They had

more money, more time, more common sense and much more to write about than

youngsters had.

Blinking

Eye Publishing promotes the work of writers over the age of 50.

- Fear of too much work - Don't know where to start? The Writers and Artists yearbook lists hundreds

if not thousands of addresses. It's hard to know where to begin. Keep listening

...

I stopped being a passive reader

and realised I could be part of "the printed world". I read actively, asking

myself "could I do better than this?". After that, I

conquered my other inhibitions without too much trouble.

I mostly do literary stuff.

Every few months I plan ahead. I look

- at forthcoming competition deadlines (they're inflexible, so I consider those first)

- for magazines that I've not sent to for 9 months

- for my pieces that deserve to be published

It helps to know whether magazines will reply in days or months. I've a

group of magazines that I regularly sent to, so I know what to expect. Every so often I try a new one.

For articles, poetry and prose, look out for themed issues of general

magazines. Sometimes the only way to find out about these is to read the

magazines, though often the magazine's web pages help. Also check for forthcoming anniversaries, especially when you can tie them with

some contemporary event. Remember that magazines often

plan months ahead.

Good publishers

are never short of authors, so don't bother replying to adverts in the

press. The details about sending off vary a lot depending on the genre. An SAE is usually

obligatory if you're not using the web or e-mail. There's no excuse - when Masefield was poet laureate he sent his official poems to the Times, even he included a stamped return envelope in case of rejection.

Good publishers

are never short of authors, so don't bother replying to adverts in the

press. The details about sending off vary a lot depending on the genre. An SAE is usually

obligatory if you're not using the web or e-mail. There's no excuse - when Masefield was poet laureate he sent his official poems to the Times, even he included a stamped return envelope in case of rejection.

Poems and stories

There's is big split between literary and general outlets.

- Literary -

The UK literary world is tiny.

Don't think about sending a book off until you've had many

pieces accepted.

Remember, you're in competition with students from hundreds of Creative Writing

courses whose homework includes having to submit work to magazines, so you can't afford to be amateurish.

- Where? - don't aim too high or too low. League tables aren't easily

obtained. For US magazines there's Jeff Bahr's US

poetry magazine ratings which gives information like the following

For literary outlets Duotrope lets you search markets by genre, word-length, etc. Or you can try Word Hustler.

In the UK see

The lists might look long, but many of the magazines come and go. Focus on the

long-standing magazines, or magazines that you like. A UK list of

worthwhile, feasible outlets for stories in print might have 5 mags. Tania Hershman keeps a list of UK literary story outlets (111 mags at the moment). For poems, 10-15 is a

more reasonable number. See

the Happenstance

list of reputable publications

for ideas.

I wouldn't bother sending to competitions until you have a fair idea of what's

likely to succeed.

- How? - see submission guidelines. Some magazines are fussier than others,

especially regarding multiple submissions, but you can't go too far wrong if

you send a story or 3 poems along with a biographical note and SAE.

- What? - read magazines and judge's reports. One of the most common reasons for a piece being rejected is that it's inappropriate. Some editors have pet

dislikes and quirks (yet another poem about Paintings, yet another story about

Alzheimer's, etc). Remember that editors like to provide variety, so throw in

the odd joker. Larkin said that the poem he included in a submission "to make

the others look good" was often the one that was accepted.

- "Bio" and covering letter - I don't include a covering letter unless the

guidelines say so or I'm sending to a magazine for the first time. Ditto

with biographical notes. I keep them

simple (town, family status, profession, recent publications) unless they

specify otherwise. I keep

a lit

CV online.

If you write a cover letter -

- Try to name the person you're sending to (don't use "Dear Sir")

- Say what's in the submission

- Say why you chose to send it to that particular place

- Give a brief bio and summary of past writing experiences

- If it's appropriate, say how you might promote the resulting

publication

It's worth spending time on your bio because it might be published and it can affect the likelihood of your work

being accepted. E.g.

- The guidelines for "Anti-" magazine says - "Include a cover letter with your name, contact information, a contributor-note biography of 50 words or less, and a statement of 50 words or less on what you're against in poetry. This statement can be general or specific to your submitted poems, serious or tongue in cheek, broad or ridiculously minute."

- The guidelines for the recent "Woman and Home" Short Story competition (the theme was PASSION) asked for a story of max 2500 words, a recent photo, and 200 words about yourself.

- "Horizon Review"'s submissions guidelines say that You must include a

75 word biographical note

- The 1st ten seconds - many pieces are rapidly rejected. Make sure your work

doesn't fail at the first hurdle. Think speed-dating.

- Avoid vanity press!

If an editor's giving a talk it's useful to attend. You'll get a better idea of

how they sift submissions and how ruthless they have to be. Here's what one UK small-press publisher wrote in 2013 about book submissions - "I know within a few sentences or lines whether I want to read on. If I don’t, I try to delay my reply for at least a few days, so that the sender can preserve the illusion that I’ve read the whole book, on which they may have laboured for years".

- Non-literary -

Suppose you've written a humorous poem about Allergies. If stuck-up literary

magazines reject it, look for non-literary opportunities. You might get published in Readers

Digest, New Scientist, Men's Health, Supermarket magazines, etc. There's

a literary magazine that's designed for doctors' waiting rooms. Letters columns are a useful

way in to magazine publication.

Novels

Different rules apply! Get an agent! See

a list of literary

agents. Alternatively enter a competition where the winner has their book published.

Some magazines print chapters nowadays.

Preditors & Editors is "a guide to publishers and publishing services for

serious writers". It has examples of cover letters, legal advice and much else besides.

Articles

A huge market, one we should take more advantage of. Maybe the easiest thing to do is to idle in a newsagents for a

while and browse through the magazines that interest you. Again, it's a matter

of getting into the right mindset and becoming an active participant in the

print-world. The money's often good, and you may not need to work too hard -

exploit what you know rather than research. Use your past as a library.

Years ago I was asked to write an article about 'Children and Allotments' for a

proposed local leaflet. It didn't take long to write. The leaflet wasn't

produced in the end, so I put the article online. Where could I have sent it

instead?

Since then

- A Sheffield organisation found it and asked if they could use it.

- "Home and country" magazine found it and asked if they could use it.

- 2 TV companies have been in touch (Look East visited!)

- I've seen articles in Sunday supplements, food magazines. When

Harrods publicised their roof garden, several spin-off articles appeared.

'Bricks and Mortar' (Times) had 2 pages about

allotments, showing how they save money now that food prices are rising.

No doubt Saga magazine, parenting magazines, and health magazines regularly deal with the topic,

etc.

- The new

towns in our area have brought community garden and allotments into the news.

2 of the 4 candidates in the local Trumpington elections mentioned their

allotments in their literature!

- The Dept of Architecture and a Cambridge Art Gallery both had exhibitions

about allotment buildings

The opportunities are there. It's all up to you! I think it's easiest if you're

already a specialist in something - it's easier to adapt what you know than

learn something new - but there are many outlets for common topics too.

Many magazines have Travel

sections (gone for a walk recently?), food sections and book sections.

Or you coud just string together some things you like and call the

article "50 reasons to be cheerful" or "5 best things to do" (both of

these appeared in a recent issue of "Good Housekeeping"). Several magazines

don't accept freelancers though - read the guidelines or "Writers and Artists".

As Jane Wilson-Howarth's pointed out, a headline-grabbing title's very useful.

Don't neglect foreign markets - your knowledge of UK small literary magazines,

or Cambridge, or pubs, may not be exceptional but some people in Canada for

example may be interested.

And don't forget that you can use ideas more than once - if for example you get

lost on holiday, you can use the episode in a travel article, a story, or a letter.

Exercise: List some skills or life-events that could be made into an article. Done

anything strange? Anything you learnt something from? Any dinner party

anecdotes you could write up? If your partner's trying to impress some new

acquaintances, what do they say about you? What did your parents say to

humiliate you when you brought a new friend home? How do your children describe

you to their friends? What will be written on your gravestone?

Reviews

There are shortages of reviewers sometimes - magazines (especially small

literary ones) sometimes advertise for them. Rattle magazine (in the US)

have an online list of book that they'd like reviewed. If you ask for one

they'll send it to you as long as you send them back a review.

Send off samples (preferably previously published ones) in the first instance.

Some people say that it's relatively easy to get reviews accepted, and that

they lead to

other opportunities.

Electronic submission to paper-based magazines is cheap and fast, but you

still need to do your homework. Don't be sloppy! Many American magazines

offer an online submission facility where you need to register first - you'll

need to fill in a form but but it's nearly always free, and offers benefits.

For example, you'll be able to track the progress of your submission and

perhaps look at your record of previous submissions. On the right you'll see

my attempts to be published in "Quick Fiction".

Electronic submission to paper-based magazines is cheap and fast, but you

still need to do your homework. Don't be sloppy! Many American magazines

offer an online submission facility where you need to register first - you'll

need to fill in a form but but it's nearly always free, and offers benefits.

For example, you'll be able to track the progress of your submission and

perhaps look at your record of previous submissions. On the right you'll see

my attempts to be published in "Quick Fiction".

The web offers new writing opportunities, a foot in the door on the way to

paper-based publication. Web-only publications are increasingly

respectable (selections from online magazines are now regularly included in the Best American Series of annual anthologies; online editors can nominate their contributors for the Pushcart Prize; the National Endowment for the Arts permits up to half of one's qualifying publishing credits to be from online journals). Even if you self-publish on the web it can lead to recognition -

for example,

the BBC have interviews with people whose only qualification appears to be that

they publish a blog.

Don't send to the same place too often (Iota magazine said that one year a poet sent them 68 poems!). Don't send the same piece to the same mag (editors have excellent memories!). I keep

- a spreadsheet of who's rejected what

- A list of when I've last sent to each magazine

- A list of what's in the post

See my list

of what's in the post (messy, but it does the job). I guess I average about 10 pieces in the post at any moment. Sometimes I have 30 pieces in the post.

To help me analyse my progress

I make graphs

of my results.

For literary outlets you could use an online database like Duotrope.

Not only will this help you track your submissions, but the response time, etc, is added to a database so that all Duotrope users can get an impression of how long they might need to wait.

So you've read the magazines, prepared your manuscript, sent it off, filled in your spreadsheet. After a few weeks you notice an SAE on the doormat ...

The odds are rarely much better than 1 in 50 even in literary backwaters, so brace yourself.

Of course, editors can have legitimate reasons for rejecting good work - they

really might be full; maybe they really do have another piece dealing with exactly

the same topic - but it's depressing all the same. There are many instances of

classics (e.g. the first Harry Potter book) being rejected many times, so it's

worth being stubborn. Less

well advertised (and far more common) are the self-styled "neglected geniuses" who waste time and money

bashing their heads against brick walls. I once

had a poem accepted on the 15th attempt ...

If a piece repeatedly fails, maybe you should think about sending it to

a different kind of outlet altogether. If the BBC turns your play

down you could perhaps make it into a school play or a Whodunnit evening. Your

failed novel for adults might be a blistering success with Young Adults.

People who send off material with autobiographical elements have particular

trouble with accepting that it's not their soul being rejected, just their

piece of writing.

Even battle-hardened writers get hurt by rejections. E.g.

- I don't like receiving 2 rejections in a day. It happens.

- With e-submissions, e-rejections can arrive any when, even Sundays.

- I once got an acceptance from a mag with a note asking me to send more on

straight away. The editor later replied saying something like "thanks, I'll

stick with the first one"

- Some rejections make me wonder what else I could do - "This is

a great read - it's extremely entertaining and very witty. I don't think

it's quite right for ..."

In the US there are agencies who will do the submitting for you. There's also

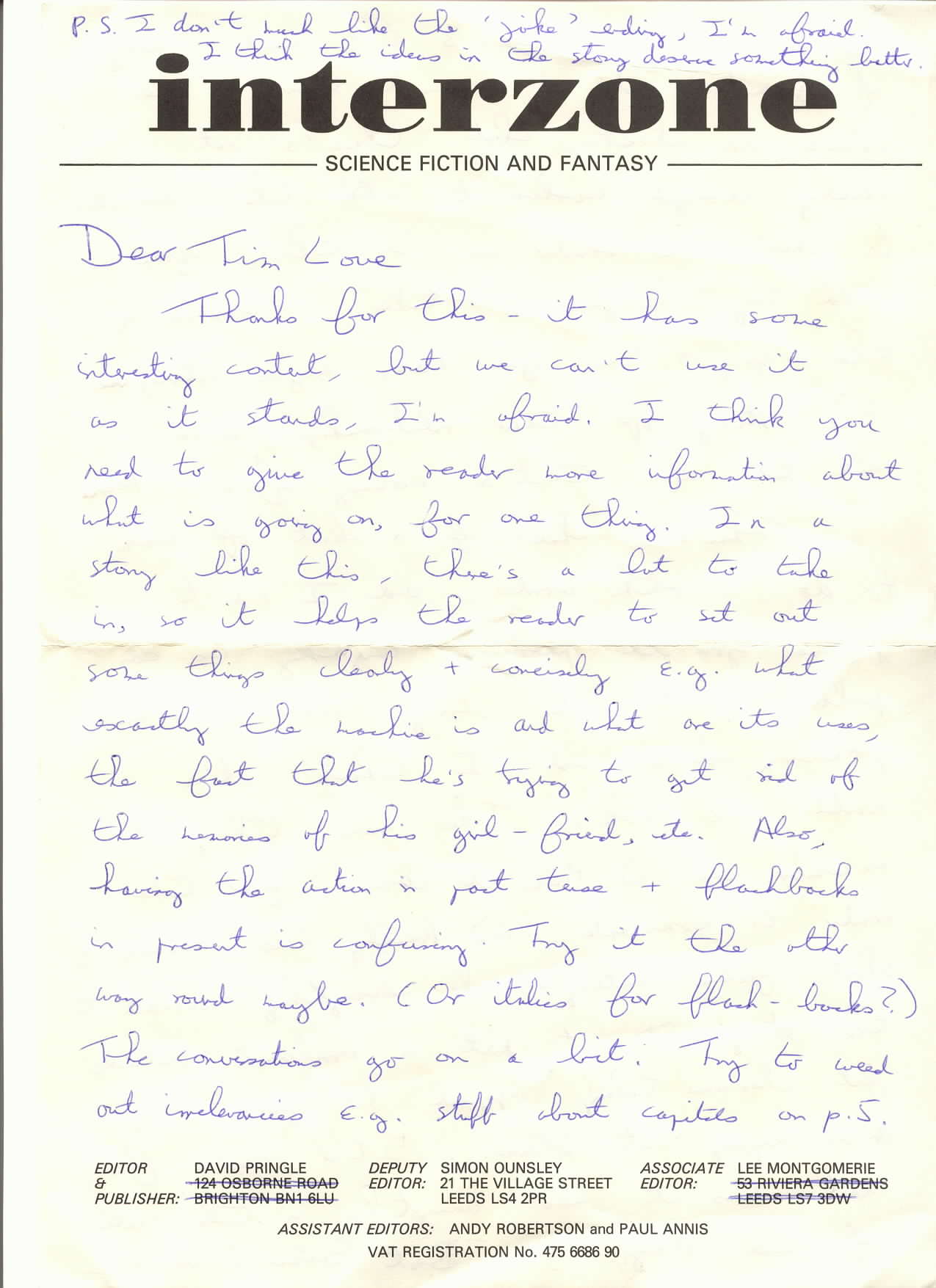

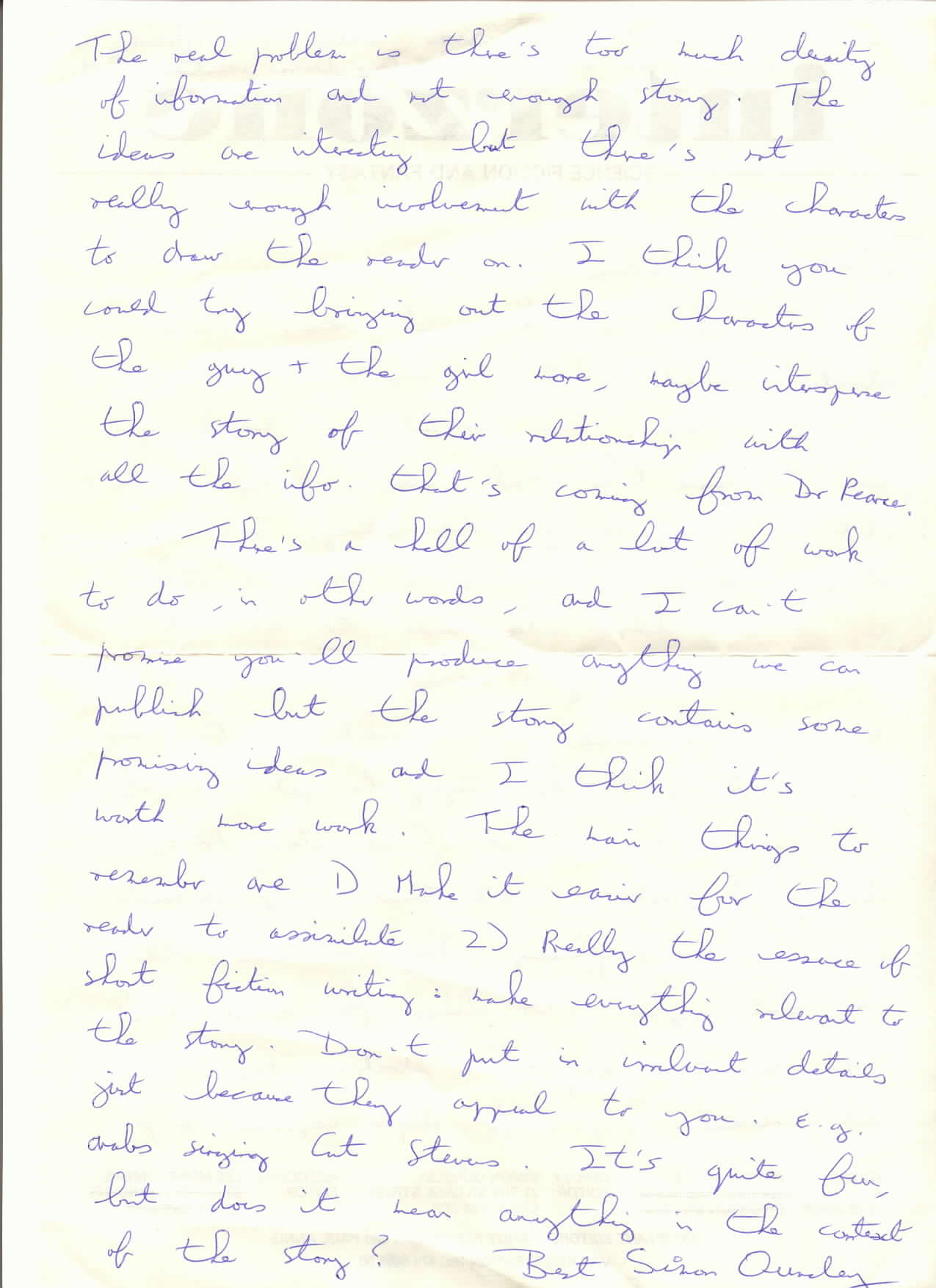

Anything other than a standard printed rejection slip (as from the New

Yorker below) is progress. I once received a rejection letter which was 2

packed A4 pages long, from Interzone

Below is a more recent (2008) rejection I received. It softened the blow

Thank you for sending us three of your poems for consideration for Magma 42.

I have now been able to read and re-read them a number of times and I've

enjoyed much in them. They respond very interestingly to the issue's theme

of engagement with feeling and I've held on to them till now in the hope of

being able to take "Believing in myself".

However, I'm afraid this isn't going to be possible. The response for Magma

42 has been enormous, greater than usual, and we've received well over 2500

poems. With the pressure on space, it won't be possible to take one of your

poems, but I thought you might like to know it was a near miss.

It's worth holding on to rejection slips - the editors might become famous.

Here are 4 of the rejection slips I got from David Almond ("Skellig", etc).

It's worth holding on to rejection slips - the editors might become famous.

Here are 4 of the rejection slips I got from David Almond ("Skellig", etc).

Occasionally one gets rejections like this -

Remember Goethe's advice to the misanthropic young Schopenhauer ... if you wish to enjoy (your) life, then you must ascribe value to (love) this world (as it is). Somehow you need to get out of yourself, your intellectual self.

Some online mags offer detailed rejection slips. Here's one I received

Editor 1 Vote: Maybe

Ed. 1 Comments: I feel like I'm on a tour run by the Ghost of Christmas past.

Editor 2 Vote: No

Ed. 2 Comments: Too much distance from the subject

Editor 3 Vote: Yes

Ed. 3 Comments: Pulls its strands together nicely.

Editor 4 Vote: Maybe

Ed. 4 Comments: Intriguing.

Editor 5 Vote: Yes

Ed. 5 Comments: Great sense of style and voice.

Editor 6 Vote: Maybe

Ed. 6 Comments: I like the writing, but I'm not sure I understand what's going on.

Here are some tricks I've used to lessen the pain

- As part of your planning, assume a piece will be rejected and have a place

ready to send it to next - bounce it straight out again without brooding

- Use personal and embarrassing material in your work so that you'll be

secretly relieved when it's rejected

- Have someone else open the envelopes.

- Rejoice! One acceptance can make up for handfuls of rejections

- Success breeds success - you become more confident; editors recognise your

name; and you can add more to covering letters. Once you've published your

novel you can write articles about how you did it!

You'll be expected to write a bio if you've not already done so. Here are some

examples

- Catherine Smith's The New Bride was shortlisted for last year's

Forward First Collection. Very drunk on her own hen night she sang her way down

Streatham High Road. She is still married (Rialto)

- Sarah Oswald writes fiction inspired by places. She grew up in Canada,

lived as a traveller, spent many years in Wales and now lives in Devon.

It's her

ambition to write something as beautiful and disturbing as walking on Dartmoor

in the rain with no map and a podful of ISIS ... (Riptide)

- Erik Campbell: "One afternoon in the summer of 1994 I was driving to

work and I heard Garrison Keillor read Stephen Dunn's poem "Tenderness" on

The Writer's Almanac. After he finished the poem I pulled my car over and

sat for some time. I had to. That is why I write poems. I want to make

somebody else late for work." (a sample from Rattle's submissions page)

Exercise: Write a bio. It can be straight or wacky. Max 75 words. Say what

sort of magazine/publisher it's for.

If you have a book accepted, don't expect book-shops (even independent

bookshops) to stock it, though you're welcome to try. Organise a

local launch (in a bookshop perhaps) and organise some readings. You

could organise for several blogs to feature you as part of a "tour".

For poetry at least, don't expect adverts and reviews to help. Here's what the

Shearsman editor wrote in 2010 - "I used to advertise, but found that it had no impact on sales. In fact, when I cut advertising completely, sales went up by 25%. This suggests that the only kind of marketing that works is the targeted variety. Reviews generate very little sales, although a generous notice in the TLS will have an impact that is immediately noticeable. The same holds for Ron Silliman's blog."

When should you start chasing up? I never have. Some literary magazines

take several months to reply anyway. Check first that you've read the

guidelines - some magazines warn that if you send at the wrong time of year, or if

you include insufficient postage, you won't get a reply. Others (especially if

you submit by e-mail) say that if you don't get a reply within a month,

you've been rejected.

If you don't get paid, well, eventually there's the Small Claims Court.

Sounds too much like hard work?

Here are some alternatives

- Become a celeb first, then publish later - see Viggo Mortenson

- Apply for all the grants/awards you hear of. The Society of Authors

and Regional Arts Boards can help. If you're young enough, try for a Gregory

award.

- Try to get into any book you can. Some Regional Arts Boards fund

anthologies. Find out what themed anthologies publishers are planning.

- Going to Arvon courses helps to meet the right people.

- Go to conferences. Mingle at coffee breaks.

- Put aside money to regularly enter the main annual competitions - Bridport (Poetry and Prose),

National Poetry Competition, Peterloo Poetry Competition. Unknowns can win these.

- Consider WWW publications, local radio.

- Establish yourself in a niche market (SF, short-story reviewing, U3A workshops,

etc) then

"go transcendental"

- Find a gimmick. If you can sell 100 or so copies on the strength of

radio interviews, press releases, you're viable. So corner the market on

football poetry, allotment poetry, stories about twins.

Looking back, the mistakes I made were mostly to do with investing too

little, too late. I should have more quickly subscribed to magazines (I didn't

know they existed until my mid-twenties), went to a residential workshop run by

a magazine editor, and entered competitions with more dedication.

(At the end, ask each

person what they're going to do - pieces they're going to write/adapt, research

they're going to do.)

Good publishers

are never short of authors, so don't bother replying to adverts in the

press. The details about sending off vary a lot depending on the genre. An SAE is usually

obligatory if you're not using the web or e-mail. There's no excuse - when Masefield was poet laureate he sent his official poems to the Times, even he included a stamped return envelope in case of rejection.

Good publishers

are never short of authors, so don't bother replying to adverts in the

press. The details about sending off vary a lot depending on the genre. An SAE is usually

obligatory if you're not using the web or e-mail. There's no excuse - when Masefield was poet laureate he sent his official poems to the Times, even he included a stamped return envelope in case of rejection.

Electronic submission to paper-based magazines is cheap and fast, but you

still need to do your homework. Don't be sloppy! Many American magazines

offer an online submission facility where you need to register first - you'll

need to fill in a form but but it's nearly always free, and offers benefits.

For example, you'll be able to track the progress of your submission and

perhaps look at your record of previous submissions. On the right you'll see

my attempts to be published in "Quick Fiction".

Electronic submission to paper-based magazines is cheap and fast, but you

still need to do your homework. Don't be sloppy! Many American magazines

offer an online submission facility where you need to register first - you'll

need to fill in a form but but it's nearly always free, and offers benefits.

For example, you'll be able to track the progress of your submission and

perhaps look at your record of previous submissions. On the right you'll see

my attempts to be published in "Quick Fiction".