The Bayeux Tapestry is a famous example of how to display a narrative graphically. The method translates easily to prose (and movies). But there are other ways. Here I'll pursue a particular thread of narrative development in art from the medieval to the 20th century, showing how the various ways might be used in literature.

The Bayeux Tapestry is a famous example of how to display a narrative graphically. The method translates easily to prose (and movies). But there are other ways. Here I'll pursue a particular thread of narrative development in art from the medieval to the 20th century, showing how the various ways might be used in literature.

- Simultanbild

- In paintings like Hans Memling’s "Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ" several scenes have been integrated into a single landscape. Typically, the main character appears several times. For example, if the life of Christ is being presented, there might be a landscape where Jesus appears with John the Baptist in a river that passes by a hill where he's on a cross, with cows walking down the hill to a stable where he's being born. Unless one already knows the story, one couldn't put the scenes in order.

- In paintings like Hans Memling’s "Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ" several scenes have been integrated into a single landscape. Typically, the main character appears several times. For example, if the life of Christ is being presented, there might be a landscape where Jesus appears with John the Baptist in a river that passes by a hill where he's on a cross, with cows walking down the hill to a stable where he's being born. Unless one already knows the story, one couldn't put the scenes in order. - Individual Scenes

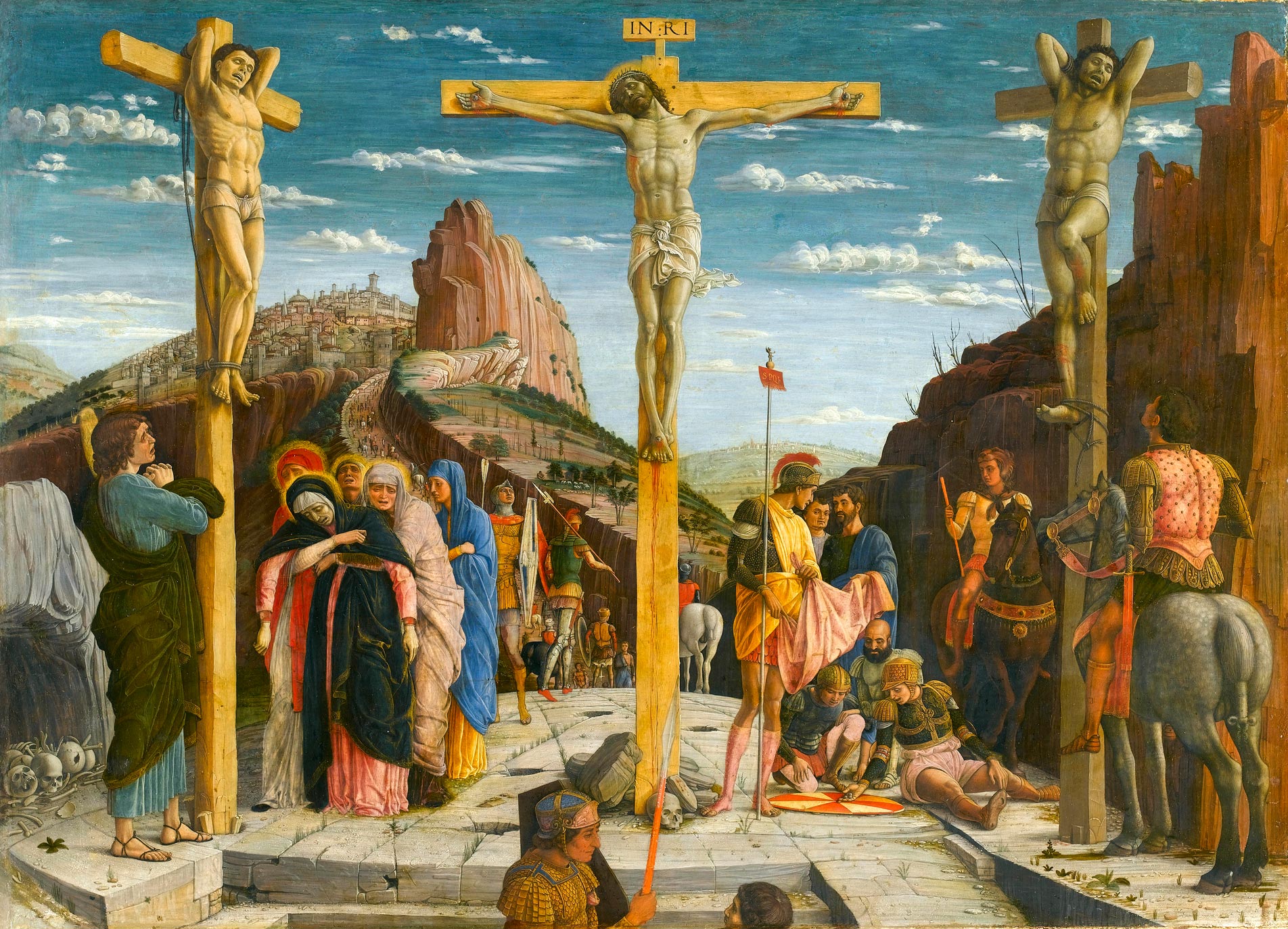

- The development of perspective and the new possibilities of oil paint led to a concentration on individual scenes. Key moments from a known narrative were presented, enriched by symbolism and allusion to past/future events - scenes with Jesus might have a carpenter's tool in the corner, and a three-legged stool represents the Trinity. In contrast with Simultanbild, Realism might be a desirable feature. Before long, the narrative element disappeared from the painting, leaving a still-life packed with symbolism.

- The development of perspective and the new possibilities of oil paint led to a concentration on individual scenes. Key moments from a known narrative were presented, enriched by symbolism and allusion to past/future events - scenes with Jesus might have a carpenter's tool in the corner, and a three-legged stool represents the Trinity. In contrast with Simultanbild, Realism might be a desirable feature. Before long, the narrative element disappeared from the painting, leaving a still-life packed with symbolism.

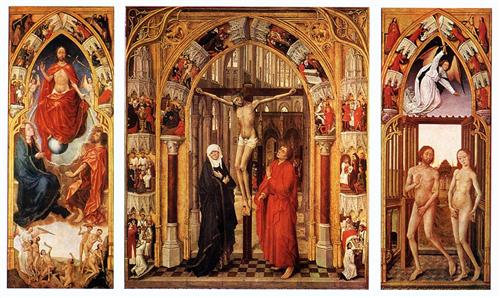

Some interiors include a window offering a view that's a picture within a picture, commenting in some way on the internal scene. - Triptychs

- 3-part works allow rich individual scenes plus the possibility of narrative sequence as in the Bayeux Tapestry, though more often juxtaposition's used, with the main central panel usually dominating the theme (it's usually bigger). The number 3 seems more popular than (say) 2 or 5.

- 3-part works allow rich individual scenes plus the possibility of narrative sequence as in the Bayeux Tapestry, though more often juxtaposition's used, with the main central panel usually dominating the theme (it's usually bigger). The number 3 seems more popular than (say) 2 or 5. - Cubism

- Just as a Simultanbild deforms a narrative, reconstructing it so that some common features (e.g. a hill) are shared by scenes, so some types of cubism deforms an object by displaying several viewpoints, organising that so that some common features (e.g. the curve of a jaw-line) are shared by viewpoints. There's no attempt to depict narrative

- Just as a Simultanbild deforms a narrative, reconstructing it so that some common features (e.g. a hill) are shared by scenes, so some types of cubism deforms an object by displaying several viewpoints, organising that so that some common features (e.g. the curve of a jaw-line) are shared by viewpoints. There's no attempt to depict narrative

All these methods can be used in literature to structure works. In some cases the analogues are straightforward and common, in others the results are rather avant-garde.

- Simultanbild - Short story collections like Kate Atkinson's "Not the End of the World" include non-chronologically-ordered stories that share characters, scenes and props. Using the idea in a shorter text is more challenging. My "What to Believe" (unpublished) and "Muse" (Staple) texts switch between story threads (often one that's historically based, and the other more personal) that use the same props. The use of a known story as one of the threads helps readers navigate through the texts, though authors needn't make it easy for readers to reconstitute the order of the scenes.

- Individual Scenes - The single scene painting reminds me of the type of short story based around a significant moment that uses flashbacks and backstories. Framed stories are a little like pictures within pictures.

- Triptychs/Cubism - Maybe my Death and Deception is a triptych. My "Three Takes" (unpublished) is rather like a triptych. Or maybe it's cubist. The same event is recounted 3 times in 3 styles. Here in particular the linear nature of reading makes it difficult to reproduce the artistic effects - seeing a triptych, an observer is unlikely to start at the left-most panel. They're likely to start at the central panel, perhaps glancing at the side panels before studying the central panel more carefully.

An interesting article. When I read it the first thing it reminded me of was Anita Brookner’s novel Family and Friends. In my article I wrote: ‘This novel is an example of what Brent MacLame calls "family album novels," a "recognizable" sub-genre of "photofiction" which he defines as a type of fiction positioning itself at the frontier of two distinct semiological codes, text and image, and exploring "the tension between the simultaneously factual and interpretative qualities of photographs."’ I know it’s a bit different to what you’re on about and if I’m being honest the Brookner was a bit of a disappointment structurally because I imagined the narrator flicking though a photo album and telling the story of each picture which would become a piece of a bigger picture, a collage I suppose.

ReplyDeleteI’m not anti-form and all my novels have a definite structure but that structure came about naturally in the process of writing. I cannot imagine sitting down and planning the novel I’m currently editing in advance but now it’s written I can’t imagine it any other way; it makes so much sense (again I’m talking structurally). I don’t write poems in traditional forms but for years now I’ve adopted a writing method that orders my poems on the page and I’m happy with it. Most of my stories are slices of life. I’m not against the beginning, middle and end approach but I rarely go down that path.

For a long time I’ve had in my head to write diptychs. I doubt I ever will but the idea of two short texts standing side by side has appealed for a long time.