When Joel Lane was a student we briefly went to the same Cambridge poetry group, though I don't think we ever appeared in the same issue of the group's "Virtue without Terror" publication (I appeared in the same issue as Alain de Botton though). I don't remember much about those days, but I remember him being one of the group's stars. His "Love Letters on Whitewash" poem sparked off my "Flapping Tarpaulin" phase. It appeared in "Second Set: Nomads" (Pendulum Press, 1986), which included work by Jean Hanff Korelitz, now a novelist and Paul Muldoon's wife. In 1993 he won an Eric Gregory Award.

When Joel Lane was a student we briefly went to the same Cambridge poetry group, though I don't think we ever appeared in the same issue of the group's "Virtue without Terror" publication (I appeared in the same issue as Alain de Botton though). I don't remember much about those days, but I remember him being one of the group's stars. His "Love Letters on Whitewash" poem sparked off my "Flapping Tarpaulin" phase. It appeared in "Second Set: Nomads" (Pendulum Press, 1986), which included work by Jean Hanff Korelitz, now a novelist and Paul Muldoon's wife. In 1993 he won an Eric Gregory Award.

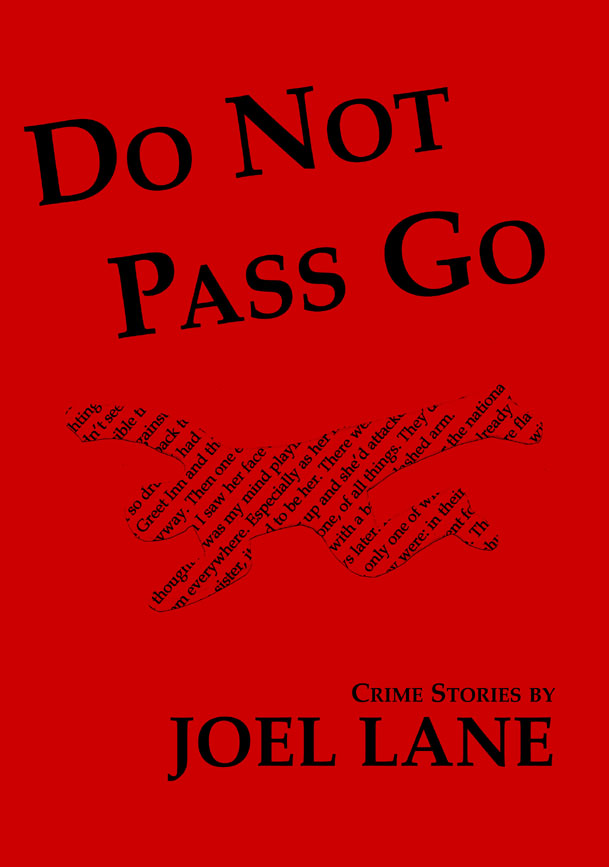

I've seen his name in magazines and anthologies ever since. Most recently, Nine Arches Press launched their Hotwire series by publishing his "Do not Pass Go" pamphlet of short stories. My "By All Means" collection will be next in the series. That, plus the realisation that he, Tania Hershman (who I've previously interviewed) and I all have science degrees and all write poetry plus prose, made me want to interview him.

First, some background information. Joel Lane lives in Birmingham and works in educational publishing. He's written two mainstream novels, "From Blue to Black" (2000) and "The Blue Mask" (2003); a novella, "The Witnesses Are Gone" (2009); four collections of short stories, "The Earth Wire and Other Stories" (1994), "The Lost District and Other Stories" (2006), "The Terrible Changes" (2009) and "Do Not Pass Go" (2011); and three collections of poetry, "The Edge of the Screen" (1998), "Trouble in the Heartland" (2004) and "The Autumn Myth" (2010). A pamphlet of his erotic poems, "Instinct", was published by Flarestack Poets in March 2012. He's assembled anthologies too.

First, some background information. Joel Lane lives in Birmingham and works in educational publishing. He's written two mainstream novels, "From Blue to Black" (2000) and "The Blue Mask" (2003); a novella, "The Witnesses Are Gone" (2009); four collections of short stories, "The Earth Wire and Other Stories" (1994), "The Lost District and Other Stories" (2006), "The Terrible Changes" (2009) and "Do Not Pass Go" (2011); and three collections of poetry, "The Edge of the Screen" (1998), "Trouble in the Heartland" (2004) and "The Autumn Myth" (2010). A pamphlet of his erotic poems, "Instinct", was published by Flarestack Poets in March 2012. He's assembled anthologies too.

In previous interviews I've asked short questions. This time some of the questions are longer

- Some people I know who write both poetry and prose are quite involved with Flash Fiction. Are you?

Not really, though I've tried that a few times. I prefer to build up a few pages' worth of character and atmosphere, though I'm all in favour of brevity. My natural story length seems to be around three thousand words. - I'm not very familiar with the genres that many of your short stories belong to. Tell me more about them. Who are the leading lights?

My two core inspirations in fiction are the supernatural horror and noir genres. The former is a wide-ranging genre that, at its best, offers a unique allegorical slant on the modern world and the human experience – some of the outstanding figures, for me, are Arthur Machen, Ray Bradbury, H.P. Lovecraft, Robert Aickman, John Metcalfe, Fritz Leiber, M. John Harrison, Ramsey Campbell and Graham Joyce. In writers like those, supernatural horror is not just a vehicle for scaring the reader: it's a modern folklore, a way of exploring the dark alleys of mortality and madness. Noir fiction is similar in its essentially dark and disturbing themes, but it uses the infrastructure of crime fiction to undermine the reader's complacency and ask questions about the way society works – see, for example, the work of Cornell Woolrich, Horace McCoy, David Goodis, John Franklin Bardin, Jim Thompson, Robert Bloch, Derek Raymond and James Ellroy. - As a student I used to change coaches at Birmingham and found it interesting. More recently I visited the centre and was disappointed, so I walked along the canal to the Ikon Gallery, then visited friends in Bournville. Where else should I go?

Digbeth Coach Station is emblematic of the new Birmingham in that it has changed from being strangely, organically unbeautiful to being merely average. Digbeth itself, the district, is well worth exploring through the old streets and factories are being cleared away as if by some quiet bomb. Walk out along the Grand Union Canal from Digbeth to Yardley or beyond, that will give you a real flavour of the older city. Also, walk through the Aston University campus and have a look at the old streets beyond it. Some great pubs there. As Roy Fisher said, you'd never get home. - You have a NatSci degree and a Philosophy of Science Masters, I think. So, incidentally, has Tania Hershman. It's become quite fashionable to mix Science and the Arts - there's LUPAS for example. I tend to notice writers who mention science/maths/computing in their bios. As well as you there's

- David Morley (post-degree)

- Mario Petrucci (Ph.D)

- Peter Howard (science degree)

- Valerie Laws (Maths/Theoretical physics)

- Michael Bartholomew-Biggs (was a computing professor)

- Kona MacPhee (computing degree)

- Stephen Payne (Professor of Human-Centric Systems)

- Tania Hershman (MSc, MPhil)

to mention just a few. I don't see any writerly trends they particularly have in common. There are varying views on the Arts/Science interaction. On the one hand there are people like Prof Robert May who think that "the essential aim of science is to understand how the world works. This is also true of the arts ... the technical trappings of science obscure its underlying kinship with the arts". On the other hand, Graham Farmelo (Science Museum, London) wrote "Be sceptical of any science-art initiative and you are liable to find yourself marked down as a narrow-minded reactionary. If a new work of art is based on a theme related to science, most critics will give it an easy ride... It seems that this flavour of political correctness encourages intellectual laziness, allowing shallow and sentimental nonsense about the relationship to pass for serious thought". I'm more on Farmelo's side. How does science enter your work, if at all? Do you regret not being the Lavinia Greenlaw of your generation ("Her work is heavily informed by her interest in science and scientific enquiry" ... "She has held a number of residencies including at the Science Museum and the Royal Society of Medicine")?

Well, surely the Lavinia Greenlaw of my generation is Lavinia Greenlaw, and wishing I was her won't help. But I know what you mean. Scientific ideas influence my writing in several ways: I'm quite preoccupied with medical and psychological themes, as well as Marxist social and cultural analysis. Never could get into post-structuralism because, coming from a scientific background, I could see it didn't engage with experience. At the same time the aggressive and reactionary 'scientism' of some of the British science establishment didn't appeal to me. The combination of scientific and cultural ideas in my own training and experience led me naturally towards dialectical materialism. And yes, there's little more embarrassing than half-baked Sunday supplement 'science' dressed up as literary insight. But to be wilfully ignorant of the importance of science in shaping our lives and the depth of understanding it offers, and to regard it as merely another arbitrary 'belief system', seems to me seriously inadequate.  How

did Do Not Pass Go come about?

How

did Do Not Pass Go come about?

Nine Arches Press, who at that time were becoming well known in the Midlands as a small poetry publisher, decided to start a new series of booklets devoted to short stories. They asked me if I was interested in submitting something for their consideration. I had a number of published but uncollected urban crime stories which I thought might make an interesting short collection with a regional basis. I offered them the best of those plus some new work, and they chose the five stories that appear in DNPG. Their editorial input was excellent, much of it having to do with awareness of viewpoint and time, and they absolutely saw what kind of tradition the stories were coming from. And as you know, the production of the booklet is superb.- Was Cambridge a good influence? How did it change you?

It was a great experience from an intellectual and academic point of view, and to some extent a cultural one, but I suffered from having very little free time or energy to devote to anything but studying. After four years I was seriously burnt out and felt I had to pursue my own life in a context where I had more time to live it. Also, I'm very much a city person, and found the small-town environment too limiting. The intensity of it helped me to develop a stronger work ethic, and I learned a lot about the power of ideas and the value of intellectual clarity. That set me up for quite rapid development as a writer once I'd returned to Birmingham. - Do you publish in US magazines? Have your books been published over there?

Quite a lot of my short stories in the supernatural horror genre have appeared in US magazines and anthologies, and the US specialist press Night Shade Books published a collection of my short stories called "The Lost District". They take short stories more seriously in the US than here, and perhaps they take genre fiction more seriously as well. My novels have been available in the US but sales have been modest. - What did you miss by not doing a Creative Writing degree/masters?

Well, to start with I got the chance to learn a tremendous amount from the degree and masters that I did, and to make that the basis of an admittedly scrawny career in science-based publishing and journalism. It's very difficult to build a career as a writer, and most writers seem to end up making most of their money from ancillary activities such as teaching creative writing. There are good people teaching these courses and good writers coming out of them – I can only say it wasn't something I could face from either side.  I was looking after a stall at a Leicester bookfair in March. Next to me was the Flarestack stall. They said that your "Instinct" pamphlet was literally hot off the press. Some of the poems in there were written 25 years ago. How has your poetry changed over the years? Are there identifiable phases and influences?

I was looking after a stall at a Leicester bookfair in March. Next to me was the Flarestack stall. They said that your "Instinct" pamphlet was literally hot off the press. Some of the poems in there were written 25 years ago. How has your poetry changed over the years? Are there identifiable phases and influences?

My poetry, like my prose, has become less lyrical and more terse over the years, less driven by imagination and more by a need to try and analyse what's going on. But it's always been a blend of outer and inner realities, of political and personal themes. There's some early stuff I now find too fanciful and some later stuff I now find too matter-of-fact, so I think an effective combination of those elements is always what I'm trying to get right. Early influences included Sylvia Plath, Thom Gunn and Allen Ginsberg. Then the poetry of the early nineties became a strong inspiration for me: Ian McMillan, Carol Ann Duffy and others. Edwin Morgan was another major influence at that time, a poet with a unique track record who was also producing astonishing new work. In recent years political activism has driven a lot of my writing, with poems trying not just to comment on events but to put across a socialist perspective – that's quite challenging as a literary approach, but I think it's important. Pablo Neruda and early W.H. Auden are fine examples of that approach, of course.

Thanks Joel!

No comments:

Post a Comment